GHOSTBUSTERS CENTRAL, THE FIREHOUSE

"You guys gotta try this pole!"

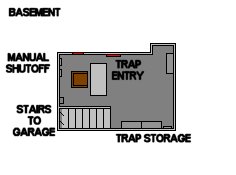

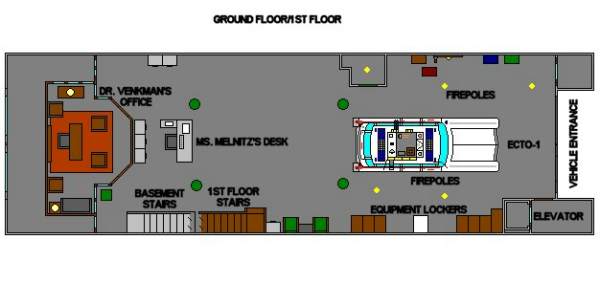

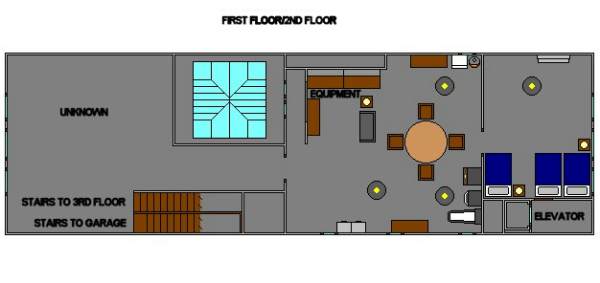

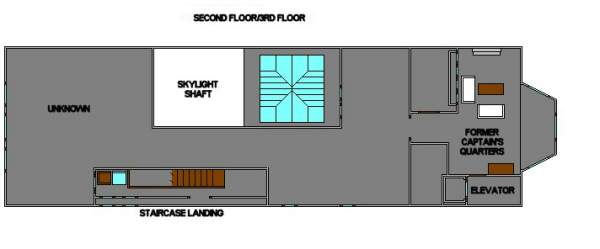

Formerly the base of the FDNY Hook & Ladder #8, the building became abandoned and went up for sale. The structure was built around the turn of the century (Around 1912.) and was built to a style widely used for firehouses during that time. The building features three floors and a basement, a full vehicle repair area, office and recreation space and fully fitted kitchen/bedroom and bathroom. The Firehouse features four brass poles, a left over alarm system and original engine doors complete with motors. In 1989/1990 the Firehouse is declared a Historic Monument after new records surfaced over it's former fire company helping prevent a ghost invasion in 1959. (It's About Time)

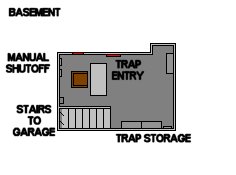

(The basement seen here is as depicted in the first movie; the animation features a much larger basement and Ecto Containment Unit)

F/N F/N (Update of 13/09/04)

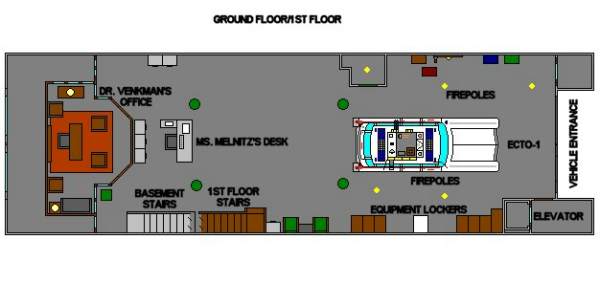

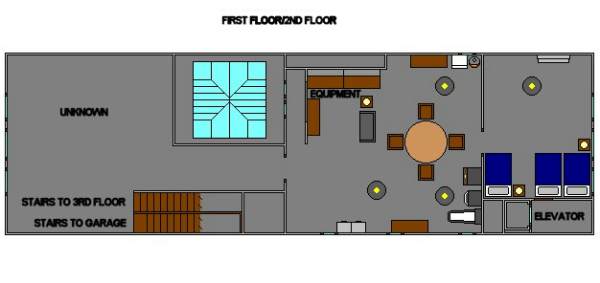

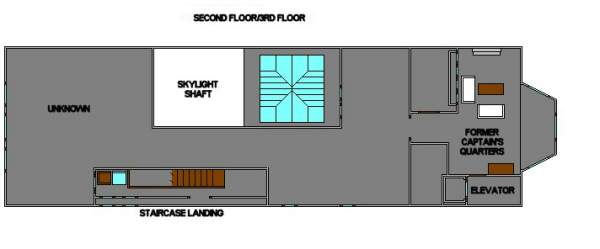

While originally described as a layout discrepency, recently take photos have revealed that the layout of the Firehouse is a lot more complex then originally thought, as illustrated by the revised set of floorplans. The ground floor is pretty much as theorized, the only note to make is that the large green pillars appear to be set pieces, they don't exist in the photos of the LA Firehouse and have a different design in Ghostbusters 2.

The second floor actually houses the 'bunkroom' and laboratory which housed the sensing equipment used to monitor 'Dana Barrett', the rear portion of this floor is kept out of shot, leading to the mistaken assumption. However, there is indeed a skylight on the second floor, as there is on the first floor, thanks to a massive light shaft in the centre of the Firehouse. an additional note is that the equipment lockers and the alarm housing are actually permanent instalations within the building left over from it's service days.

Additional notes include that there are four firepoles, not the theorized six, and a small shaft near the middle of the length of the building which allowed for firehoses to be held up for drainage.

The interior of the Firehouse is actually Station Company No. 23, which is of similar age to Hook and Ladder No. 8.

C/N Information gathered from The Old Firehouse. Photos of Station 23 are available at www.gbproject.com

NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

"It blew books off shelves from 20 feet away and scared the socks off some poor librarian."

Perhaps the greatest example of Beaux Arts architecture in Manhattan, the majestic New York Public Library stands proudly on 5th Avenue.

Its grand steps are flanked by the museum's mascots, two stone lions known as "Patience" and "Fortitude" which were so named by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in 1930 in recognition of the strength of the citizens of New York during the Great Depression of the 1920's.

Founded by John Jacob Astor and James Lenox, the world's greatest reference library was dedicated in May 1911.

The New York Public Library consists of four major research libraries and 85 branch libraries situated in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island. The sheer scale of the library is breathtaking. The building spans two entire city blocks and houses 88 miles of shelves.

Its collection comprises over 52 million items, including manuscripts, published books, music scores and electronically stored data, and the Periodicals Room houses over ten thousand magazines and papers from every corner of the globe. For convenience, the library has one of the world's largest databases, which is easily accessible online.

However, the richness and atmosphere of the palatial Main Reading Room really must be experienced in person. There is no electronic substitute for the library's star exhibits, which include the Declaration of Independence, written in Thomas Jefferson's own hand.

C/N The above information was researched from Essential Big Apple's page on the New York Public Library.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

"You are a POOR scientist Dr. Venkman, you have no place in this department, or this university."

Columbia University was founded in 1754 as King's College by royal charter of King George II of England. It is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States.

Controversy preceded the founding of the College, with various groups competing to determine its location and religious affiliation. Advocates of New York City met with success on the first point, while the Anglicans prevailed on the latter. However, all constituencies agreed to commit themselves to principles of religious liberty in establishing the policies of the College.

In July 1754, Samuel Johnson held the first classes in a new schoolhouse adjoining Trinity Church, located on what is now lower Broadway in Manhattan. There were eight students in the class.

At King's College, the future leaders of colonial society could receive an education designed to "enlarge the Mind, improve the Understanding, polish the whole Man, and qualify them to support the brightest Characters in all the elevated stations in life." One early manifestation of the institution's lofty goals was the establishment in 1767 of the first American medical school to grant the MD degree.

The American Revolution brought the growth of the College to a halt, forcing a suspension of instruction in 1776 that lasted for eight years. However, the institution continued to exert a significant influence on American life through the people associated with it. Among the earliest students and Trustees of King's College were John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States; Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury; Governor Morris, the author of the final draft of the U.S. Constitution; and Robert R. Livingston, a member of the five-man committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence.

The College reopened in 1784 with a new name-Columbia-that embodied the patriotic fervor which had inspired the nation's quest for independence. The revitalized institution was recognizable as the descendant of its colonial ancestor, thanks to its inclination toward Anglicanism and the needs of an urban population, but there were important differences: Columbia College reflected the legacy of the Revolution in the greater economic, denominational, and geographic diversity of its new students and leaders.

Cloistered campus life gave way to the more common phenomenon of day students who lived at home or lodged in the city. In 1849, the College moved from Park Place, near the present site of City Hall, to 49th Street and Madison Avenue, where it remained for the next fifty years.

During the last half of the nineteenth century, Columbia rapidly assumed the shape of a modern university. The Law School was founded in 1858, and the country's first mining school, a precursor of today's School of Engineering and Applied Science, was established in 1864. When Seth Low became Columbia's president in 1890, he vigorously promoted the university ideal for the College, placing the fragmented federation of autonomous and competing schools under a central administration that stressed cooperation and shared resources. Barnard College for women had become affiliated with Columbia in 1889; the medical school came under the aegis of the University in 1891, followed by Teachers College in 1893.

The development of graduate faculties in political science, philosophy, and pure science established Columbia as one of the nation's earliest centers for graduate education. In 1896, the Trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as Columbia University in the City of New York.

Low's greatest accomplishment, however, was moving the University from 49th Street to Morningside Heights and a more spacious campus designed as an urban academic village by McKim, Mead & White, the renowned turn-of-the-century architectural firm. Architect Charles Follen McKim provided Columbia with stately buildings patterned after those of the Italian Renaissance.

The University continued to prosper after its move uptown. During the presidency of Nicholas Murray Butler (1902-1945), Columbia emerged as a pre-eminent national center for educational innovation and scholarly achievement. John Erskine taught the first Great Books Honors Seminar at Columbia College in 1919, making the study of original masterworks the foundation of undergraduate education. Columbia became, in the words of College alumnus Herman Wouk, a place of "doubled magic," where "the best things of the moment were outside the rectangle of Columbia; the best things of all human history and thought were inside the rectangle."

The study of the sciences flourished along with the liberal arts, and in 1928, Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, the first such center to combine teaching, research, and patient care, was officially opened as a joint project between the medical school and The Presbyterian Hospital. By the late 1930s, a Columbia student could study with the likes of Jacques Barzun, Paul Lazarsfeld, Mark Van Doren, Lionel Trilling, and I.I. Rabi, to name just a few of the great minds of the Morningside campus.

The University's graduates during this time were equally accomplished-for example, two alumni of Columbia's Law School, Charles Evans Hughes and Harlan Fiske Stone (Who also held the position of Law School Dean.), served successively as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Research into the atom by faculty members I.I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi, and Polykarp Kusch placed Columbia's Physics Department in the international spotlight in the 1940s, and the founding of the School of International Affairs (Now the School of International and Public Affairs.) in 1946 marked the beginning of intensive growth in international relations as a major scholarly focus of the University. The Oral History movement in the United States was launched at Columbia in 1948.

Columbia celebrated its Bicentennial in 1954 during a period of steady expansion. This growth mandated a major campus building program in the 1960s, and, by the end of the decade, five of the University's schools were housed in new buildings.

The revival of spirit and energy on Columbia's campus in recent years has been even more sweeping. The 1980s saw the completion of over $145 million worth of new construction, including two residence halls, a computer science center, the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, a chemistry building, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Lawrence A. Wien Stadium, and much more. The quality of student life on campus has been a primary concern, and the opening of Morris A. Schapiro Hall in 1988 enabled Columbia College to achieve its long-held goal of offering four years of housing to all undergraduate students. A second gift from this farsighted benefactor led to the opening in 1992 of the Morris A. Schapiro Center for Engineering and Physical Science Research, which is helping to secure Columbia's leadership in telecommunications and high-tech research.

On the Health Sciences campus, a generous commitment from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation has lent impetus to the development of the Audubon Biomedical Science and Technology Park by providing funds for construction of the Center for Disease Prevention. In addition to securing Columbia's place at the forefront of medical research, this project will help spur the growth of the biotechnology industry in New York City, forge vital new links between Columbia and the local community, and help to revitalize the area around the medical center.

Thanks to concerted efforts to place the University on the strongest possible foundations, Columbia is approaching the twenty-first century with a firm sense of the importance of what has been accomplished in the past and confidence in what it can achieve in the years to come.

The Columbia University Campus in 1897, the University moved from 49th Street and Madison Avenue, where it had stood for fifty years, to its present location on Morningside Heights at 116th Street and Broadway. Seth Low, the President of the University at the time of the move, sought to create an academic village in a more spacious setting. Charles Follen McKim of the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White modelled the new campus after the Athenian agora.

The Columbia campus comprises the largest single collection of McKim, Mead & White buildings in existence. The architectural centerpiece of the campus is Low Memorial Library, named in honor of Seth Low's father. Built in the Roman classical style, it appears in the New York City Register of Historic Places. The building today houses the University's central administration offices and the Visitors Center.

A broad flight of steps descends from Low Library to an expansive plaza, a popular place for students to gather, and from there to College Walk, a promenade that bisects the central campus. Beyond College Walk is the South Campus, where Butler Library, the University's main library, stands. South Campus is also the site of many of Columbia College's facilities, including student residences, the Ferris Booth Hall activities center, and the College's administrative offices and classroom buildings, along with the building housing the Journalism School.

]

To the north of Low Library stands Pupin Hall, which in 1966 was designated a national historic landmark in recognition of the atomic research undertaken there by Columbia's scientists beginning in 1925.

To the east is St. Paul's Chapel, which is listed with the New York City Register of Historic Places.

Many newer buildings surround the original campus. Among the most impressive are the Sherman Fairchild Center for the Life Sciences, the Computer Science building, Morris A. Schapiro Hall, and the Morris A. Schapiro Center for Engineering and Physical Science Research.

Two miles to the north of Morningside Heights is the twenty-acre campus of the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, overlooking the Hudson River in Manhattan's Washington Heights. Among the most prominent buildings on the site are the twenty-story Julius and Armand Hammer Health Sciences Center, the William Black Medical Research building, and the seventeen-story tower of the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

In 1989, The Presbyterian Hospital opened the Milstein Hospital Building, a 745-bed facility that incorporates the very latest advances in medical technology and patient care. To the west is the New York State Psychiatric Institute; east of Broadway will be the Audubon Biomedical Science and Technology Park, which will include the new Center for Disease Prevention. The Park is being developed as a major urban research complex to house activities on the cutting edge of scientific and medical research.

C/N The above information was researched from Columbia's Official Website.

550 CENTRAL PARK WEST, SPOOK CENTRAL, THE SHANDOR BUILDING

"Your girlfriend lives in the corner penthouse, of Spook Central."

550 Central Park West is an apartment building with an apposing design sat along the western side of Central Park. The Apartment Building is home to the Ghostbusters' very first client Dana Barrett, and her neighbour Louis Tully. The Apartment came under the attention of the Ghostbusters after Dana Barrett told them of the frightful incident involving her refrigerator and a "Terror Dog" which screamed the word "Zuul" at her before she slammed the door shut. After investigating the building's construction through borrowed blueprints from the hall of records, Dr. Ray Stantz is able to determine that the building's girders are cold riveted and have a pure selenium core and are made from a steel tungsten alloy, Egon is also able to determine that the roof cavity of the building is the same material NASA uses as telemetry trackers to identify dead pulsars in deep space. The building was designed by Ivo Shandor, a doctor who performed many unnecessary surgeries who in 1920 started a secret society worshipping the Sumerian god known as Gozer, Shandor setting up the cult in the belief that society was too sick to survive the second Great War. When Shandor eventually died there were almost 1000 members of the cult who conducted end of the world rituals on the building's roof. Dana's apartment is on the 22nd floor.

F/N The apartment building, while having a made up history and address, does in fact exist on Central Park West, 55 Central Park West to be exact. The Church stepped on by Mr. Stay-Puft also exists right next to 55 Central Park West. The imposing roof structure was actually an optical illusion created through matt painting and colour separation overlay, the building is only really half as tall as it is shown.

C/N Details established through the details on the Ghostbusters 15th Anniversary DVD and on The Ghostbusters Tour.

MANHATTAN MUSEUM OF ART

"It looks like a giant, Jello mold!"

The classic design of the museum holds many different areas of art, the most prominent feature being the museum's restoration wing, where priceless and rare pieces of artwork lie in different stages of restoration. The museum's latest addition is the large-scale self-portrait of a Moldavian tyrant, known as Vigo the Carpathian. During the time that the painting is stored in the museum a large amount of negatively charge Psychomagnetheric slime has built up and on December 30th, 1988.

The U.S. Custom House sits on historic Bowling Green, the area around which New York was founded. Dutch settlers built a fort on the actual site to defend themselves against first, Native Americans and then the British. In 1732, three enterprising New Yorkers leased the open area on the north side of the fort for one peppercorn per annum and made a recreational bowling green on the site. After the American Revolution in 1790, the fort was replaced by an elegant brick building, the Government House. Although intended as a home for the President of the United States, it was never used, and when the capital moved to Philadelphia, the building became the residence of New York Governors Clinton and Jay. Between 1799 and 1815, the building served as the Custom House.

In 1813, New York City acquired the building and, in 1815, sold it to a developer who divided the site, tore down the Government House, and replaced it with seven elegant row houses that were occupied by some of the City's upper middle class. By mid-century, when elegant residential neighborhoods had moved uptown, these buildings were converted into offices. Lower Broadway became known as "Steamship Row" due to the high concentration of shipping companies in the downtown area. The property was acquired by the federal government, and in 1899, the United States Department of the Treasury sponsored a competition for the design of a United States Custom House in New York that would be erected on that site. Cass Gilbert won the competition. As an architect from St. Paul, Minnesota, he saw the move to New York as a great opportunity. Later, he achieved fame by designing the Woolworth Building, which was the world's tallest building when it opened in 1913.

The U.S. Custom House stood vacant for almost the entire decade of the seventies. In 1979 Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan saved the building from demolition and sponsored a bill, which appropriated $29.4 million for its restoration. The U.S. General Services Administration held a competition for the building's restoration and re-use. After undergoing major renovation, restoration and modernization of its mechanics, the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York moved into the building on September 14, 1987 from the United States Courthouse at Foley Square. On October 30, 1994, the George Gustav Heye Center, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution moved into the first and second floors.

The original beauty of the building has been preserved and several aspects of the structure allude to the primary activity that took place within the building when it served as a Custom House, which was the collection of revenue and registration of international seas commerce in one of the world's greatest ports.

Sculptures of four of the continents, America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, by Daniel Chester French, flank the Bowling Green entrance and above the sixth story, there are sculptures representing the great commercial and seafaring powers of world history.

The huge rotunda dominates the interior of the building, which is still one of the largest public spaces in New York. This space provided a ceremonial area in which the daily bureaucratic activities of the Custom's Service took place. It now serves as a public space and is a gateway to the George Gustav Heye Center, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.

In 1936, Reginald Marsh was commissioned to execute a series of murals in the rotunda as part of the Treasury Relief Art Project, which gave work to artists during the depression. These murals have been restored to their original splendor. The larger ones display eight views of the activity at the port of New York. Eight smaller panels, depicting figures of famous explorers, are painted in grisaille to simulate statuary. The panels are considered to be one of the highlights of Marsh's career, and his work there ranks among the most significant mural cycles in New York.

The Custom House designed by Cass Gilbert was a Beaux-Arts palace for commerce. With the collaboration of artisans and artists, he left a considerable legacy of public art. It epitomizes the period in which it was designed. The turn of the last century was an era when institutions, government agencies, and corporations were expanding at a tremendous rate, when world trade increased, and great American fortunes were being made. It continues to serve as a reminder of the way architecture can respond in an inspired way to the urban environment.

Used with permission from The Palace of Commerce: The U.S. Custom House, an exhibition developed by the New York Landmarks Conservancy, based on text by Deborah Nevins.

C/N Above information researched from the U.S. Customs House, One Bowling Green New York, NY.

VAN HORNE STATION, NEW YORK PNEUMATIC RAILROAD, THE RIVER OF SLIME

"Slime! It's a river of slime!"

Once one of the main stations for a revolutionary idea for an experimental subway system, it has now fallen into decay and has stagnated for over half a century. The main feature of the pneumatic railroad was it's revolutionary idea for fan forced air trains and was built around 1870, however the system was later abandoned in favor of the now world renowned New York Subway. The pneumatic railroad, consisting of mostly illegal construction became abandoned and its inventor vanished.

F/N The NYPRR did actually exist, the station known as Van Horne is based off of the design for the old City Hall subway station, the very first station to be opened on the New York Subway. In 1870, Alfred Beach was determined to create the first subway system in NYC powered by air pressure. Using $350,000 of his own money, his crew worked for 58 days to build a tunnel 312 feet long across the street from City Hall.

The work was done in secret in the basement of Devlin's clothing store. As of this moment, I have two sources that proclaim its location in two different spots. However, the tunnel was built curving outwards into the middle of Broadway where the current R line runs, connecting the Southern block of Murray street to the South Western Corner of Warren. The tunnel was 312 feet long.

Beach opened it to the media and then the public for 25 cents a ride, impressing all but the corrupt Tweed administration currently in power within the city. Beach attempted to get support to make his Pneumatic system larger for $5 Million, but Tweed and his cronies squashed it. After Tweed was arrested, Beach tried again, but this time landlords interfered, fearing tunnelling could weaken their buildings' foundations. Beach closed his line.

Devlin's store burned down in 1878 and the rubble removed to reveal the sealed up entrance to the secret subway. It was opened once for inspection, then resealed as a new building was constructed. In 1912, those contracted to build the modern subway wanted to take possession of the forgotten tunnel, causing a legal battle with Beach's son, citing his company owned it. A portion of the tunnel was taken out to make room for the new line, but the rest exists, marked by a plaque in the now closed lower section of the City Hall station.

Ghostbusters II blended fiction with reality nicely. While their Pneumatic Transit System ran under the length of First Avenue, the tunnel work matched that used within the subway stations in the birth of the Metro Transit System. Even though the set encompassed 2 different centuries of architectural innovations, it's still one helluva ride.

C/N Thanks to ECTO-1 for the above information on the Pneumatic Transit.

STATUE OF LIBERTY

"...if she's naked under that toga, she's French, you know that?"

Sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi was commissioned to design a sculpture with the year 1876 in mind for completion, to commemorate the centennial of the American Declaration of Independence. The Statue was a joint effort between America and France and it was agreed upon that the American people were to build the pedestal, and the French people were responsible for the Statue and its assembly here in the United States. However, lack of funds was a problem on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In France, public fees, various forms of entertainment, and a lottery were among the methods used to raise funds. In the United States, benefit theatrical events, art exhibitions, auctions and prizefights assisted in providing needed funds. Meanwhile in France, Bartholdi required the assistance of an engineer to address structural issues associated with designing such as colossal copper sculpture. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (Designer of the Eiffel Tower.) was commissioned to design the massive iron pylon and secondary skeletal framework, which allows the Statue's copper skin to move independently yet stand upright. Back in America, fund raising for the pedestal was going particularly slowly, so Joseph Pulitzer (Noted for the Pulitzer Prize.) opened up the editorial pages of his newspaper, "The World" to support the fund raising effort. Pulitzer used his newspaper to criticize both the rich who had failed to finance the pedestal construction and the middle class who were content to rely upon the wealthy to provide the funds. Pulitzer's campaign of harsh criticism was successful in motivating the people of America to donate.

Financing for the pedestal was completed in August 1885, and pedestal construction was finished in April of 1886. The Statue was completed in France in July, 1884 and arrived in New York Harbor in June of 1885 on board the French frigate "Isere" which transported the Statue of Liberty from France to the United States. In transit, the Statue was reduced to 350 individual pieces and packed in 214 crates. The Statue was re-assembled on her new pedestal in four months time. On October 28th 1886, the dedication of the Statue of Liberty took place in front of thousands of spectators. She was a centennial gift ten years late.

C/N Sourced from the National Park Service entry on the Statue.

Go to

The Fact List

Questions? Comments? Go to the

Ectozone Message Board